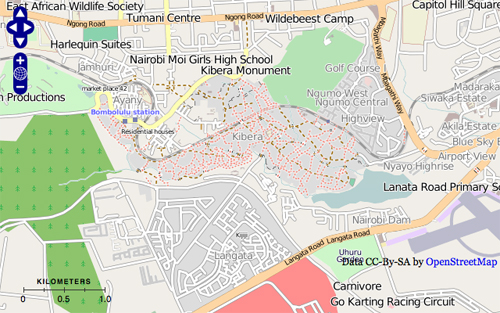

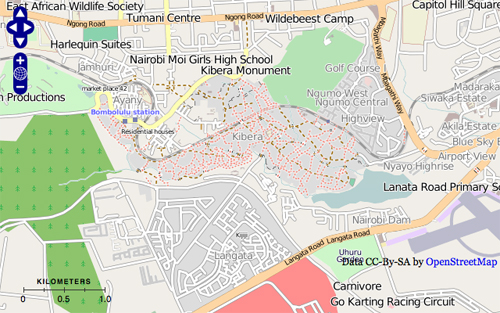

Before October 2009, Kibera, the second largest slum in sub-Saharan Africa, was a blank spot — one that had been photographed and filmed thousands of times but that no one had ever attempted to document properly.

It was at about this time that Mikel Maron and Erica Hagen, alongside a group of 13 enthusiastic youth, sought to put Kibera on the world map with the Map Kibera project. In so doing, they would provide Kibera residents and other stakeholders with a source of public, open, and shared information that would, they hoped, be used to enhance living standards in the settlement.

At that point, Kibera was completely absent from online resources like Google Maps and OpenStreetMap. This lack of basic information about geography and available resources made it much more difficult for residents and other stakeholders in Kibera communities to carry on an informed discussion about how to improve the lives of citizens there.

Approach: Identifying key thematic areas

Once a pilot map had been completed, it became clear that the team needed to develop a model for comprehensive, engaged collection of community information. Subsequent mapping focused on specific thematic areas that were considered to be of primary importance: health, security, education, and water and sanitation.

This new round of mapping added details such as operating hours and services provided by private clinics, as well as enabling the team to double-check the original data. Mappers carried digital cameras or Flip camcorders, and took photos of clinics or recorded interviews with clinicians and other health workers whenever possible.

Small community forums targeting those interested in each issue area were also conducted, at which participants were able to examine the printed maps and add comments and missing information by drawing on tracing paper over the map.

Approach: Engaging citizen journalism

To fully realize the broader vision of the project — not just a one-off map, but an engaged community mobilized around open and shared information, stories, and knowledge — it was clear that the project would have to expand and integrate the information with other technology projects and with local media.

Citizen journalism would provide a comprehensive picture of the local reality and support the achievement of community goals. To aggregate information on a map and create a platform for local storytelling, Ushahidi, an open source software for crowdsourcing information, was very helpful. Local media — including Voice of Kibera, Kibera Journal, published byKCODA, and Pamoja FM community radio, as well as a Flip camcorder video team — could map stories. These community media are the only outlets that cover Kibera from within and are a vital source of news.

Outcomes: Kibera Mappers, residents, and the international community

Apart from the obvious acquisition of new skills in using computers, video editing, citizen journalism, and new technology (GPS), several Map Kibera volunteers now have new social skills and greater comfort in public speaking and encountering strangers. This is both within Kibera, where they have had to reply to general inquiries about the activity, and in greater Nairobi, where they have been invited to participate in functions such as meetings and conferences about technology (Ushahidi Day, 1% Club, TEDx Kibera).

The mapping project itself was well received from the start by local organizations. There has been no resistance to the concept from CBOs, NGOs, or local government. Whether viewed as technology skill training for those on the other side of the digital divide, a way to get important and accurate data, a potential tool for the advocacy work of the organization, or just a practical way for visitors to find their way around in Kibera, the project has been widely embraced as the realization of something previously missing, yet clearly fundamental: the right to exist on a map.

Many have requested the paper map, which is in production. While the separation from greater Nairobi and its corridors of power cannot be overstated, the map seemed to bring the community closer to legitimacy and give a sense of being a real neighborhood.

Sensitive to external perceptions and Kibera’s negative reputation, Kiberans appreciate any image that portrays it in a positive (or at least “normal”) light, and this map does exactly that. (This is a constant subject for debate; for example, see “On Kibera, flying toilets and poop.”)

Local organizations are keen to be represented and eager to learn how they can make use of the map — as well as the Voice of Kibera web site — to highlight their activities. (Only foreign journalists seemed to think of it as a politically subversive activity or a potential tool of state control.)

It is important to note that data collected is also being reused daily in different international contexts. Groups with an interest in a variety of issues — including health, gender-based violence, sanitation, new mobile phone services, large-scale conflict mapping, and peace promotion — have contacted the directors to look into collaboration or use of collected data, sparking new thinking on each issue and the potential for the project to move in unexpected directions.

This post was originally posted on http://urb.im and has some exerps from Erica Hagen one of the Map Kibera Trust founders http://wiki.ikmemergent.net/index.php/Workspaces:The_changing_environment_of_infomediaries/Map_Kibera